This is the second of a four-part series on mortgage forbearance in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic. Last week, we provided an overview of forbearance: how it works and who was most likely to enter and stay in forbearance.

Today, we look at the behaviors of those who entered forbearance.

IMPACT ON MORTGAGE DELINQUENCY

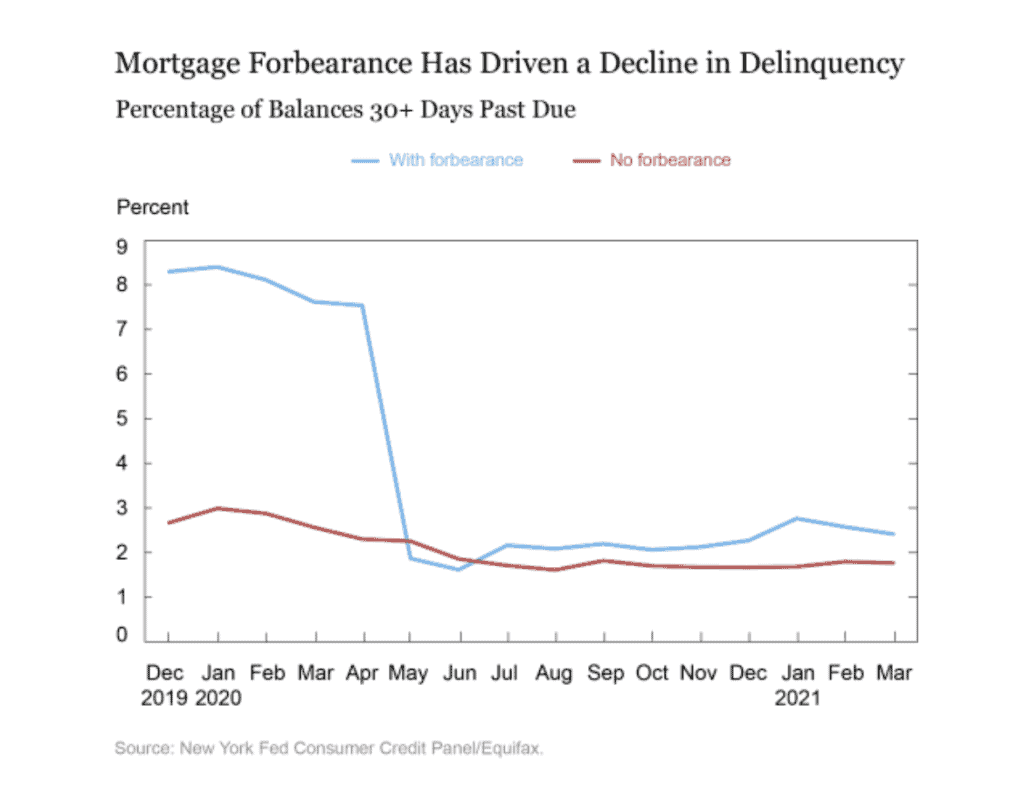

In last week’s post we mentioned that homeowners who entered forbearance were more likely to have been delinquent on mortgage payments prior to the pandemic, as compared to the average mortgage holder.

The advantage of going into forbearance, particularly for those with delinquent accounts, is that their status changed to “current” as soon as they entered forbearance. In effect, forbearace temporarily eliminated their mortgage delinquencies.

Let’s look at the chart below for more details. As you can see, more than 8 percent of those in forbearance were in some level of delinquency dating back to December, 2019. In May, 2020, with the help of forbearance, the majority of those delinquent accounts were not reported as current. Still, about 30 percent of those previously-delinquent accounts maintain that delinquent status, reflective of specific policies of mortgage servicers.

It is worth noting, according to the New York Fed’s Consumer Credit Panel, that between 30-40 percent of borrowers who entered forbearance continued to make their monthly mortgage payments.

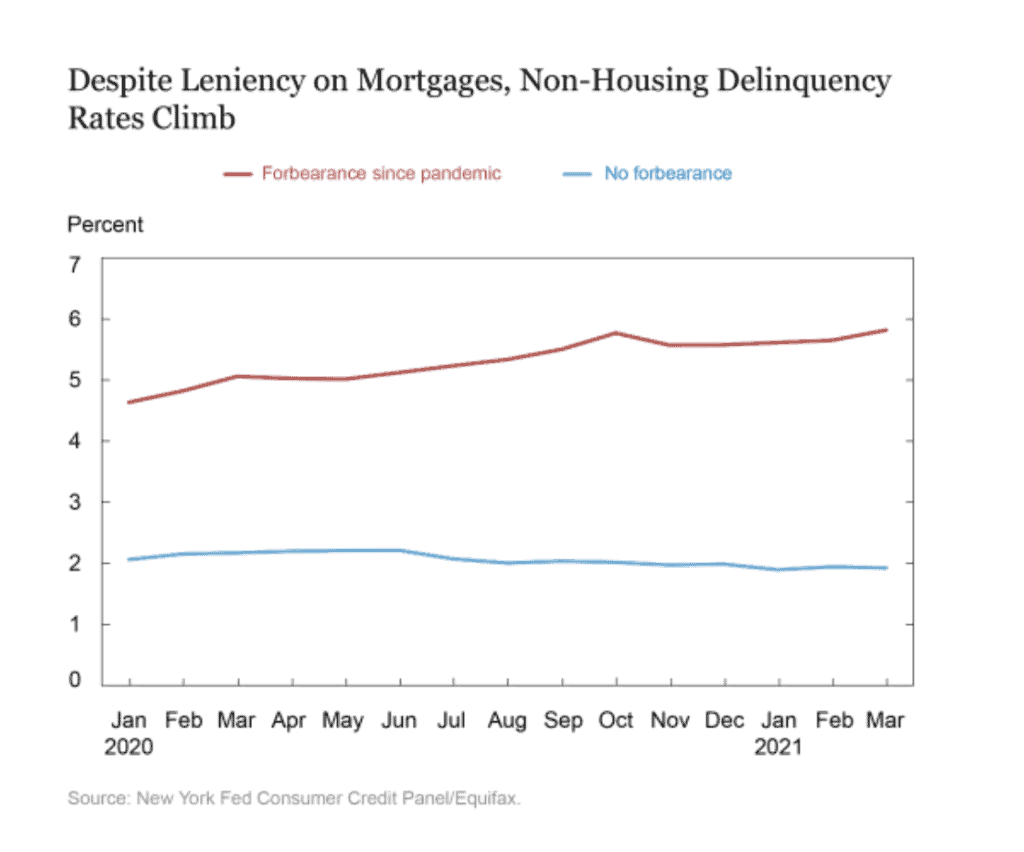

FORBEARANCE AND NON-MORTGAGE DEBT

Interestingly, as we see in the chart below, non-mortgage debt (auto, credit card, other consumer credit, but not student loans) was consistently higher for those who entered into forbearance. In fact, as of March, 2021, delinquency on non-mortgage debt was a full percentage point higher than it was in March, 2020. So, while mortgage forbearance was an important lifeline, helping many consumers to hold on to their homes, it could not alleviate the broader financial stress many of them were experiencing even before the start of the pandemic.

FORBEARANCE AND CREDIT CARDS

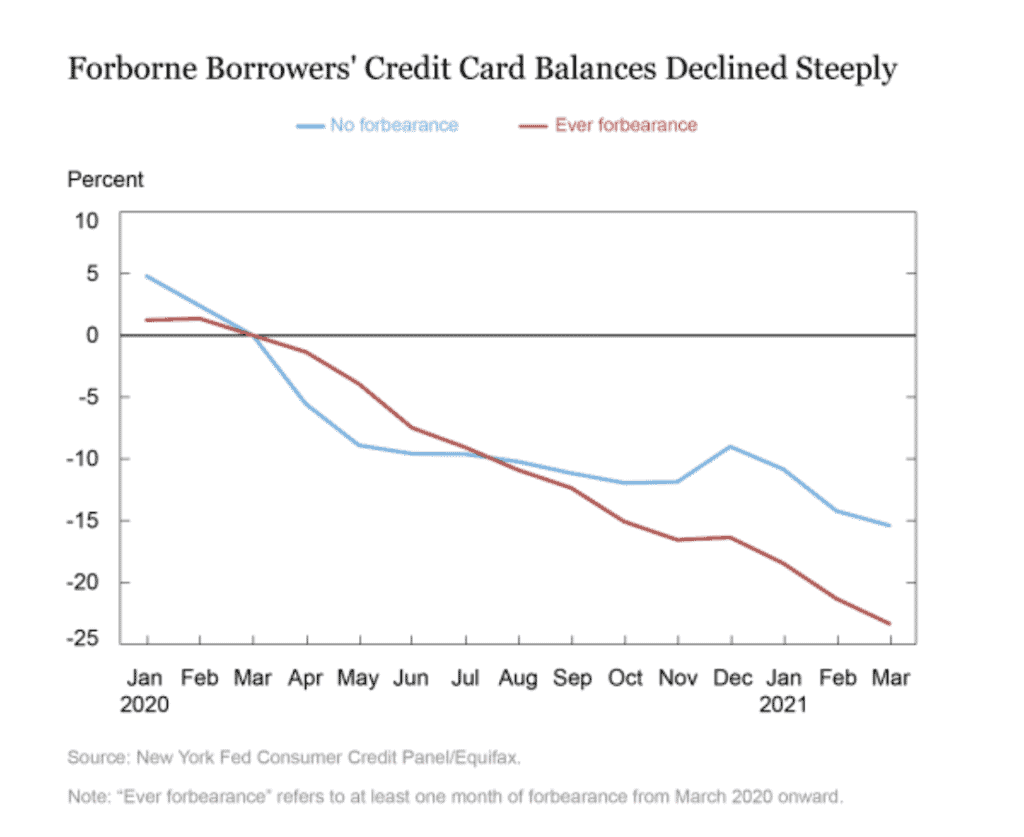

Another interesting aspect of the forbearance story is that, overall, credit card balances declined significantly over the past year, regardless of forbearance status. To a large degree, this drop was fueled by the significant drop in consumption opportunities, especially for entertainment, travel and restaurants.

As the chart below shows, credit card balances for those who entered forbearance declined 23 percent since March, 2020. This compares to a 15 percent decline in balances for those who did not enter forbearance.

In absolute terms (not shown), those households in mortgage forbearance reduced their monthly credit card balances by $2,100, from $9,000 to $6,900. For non-forbearance households, their balances fell from $6,000 to $5,100 over the past year.

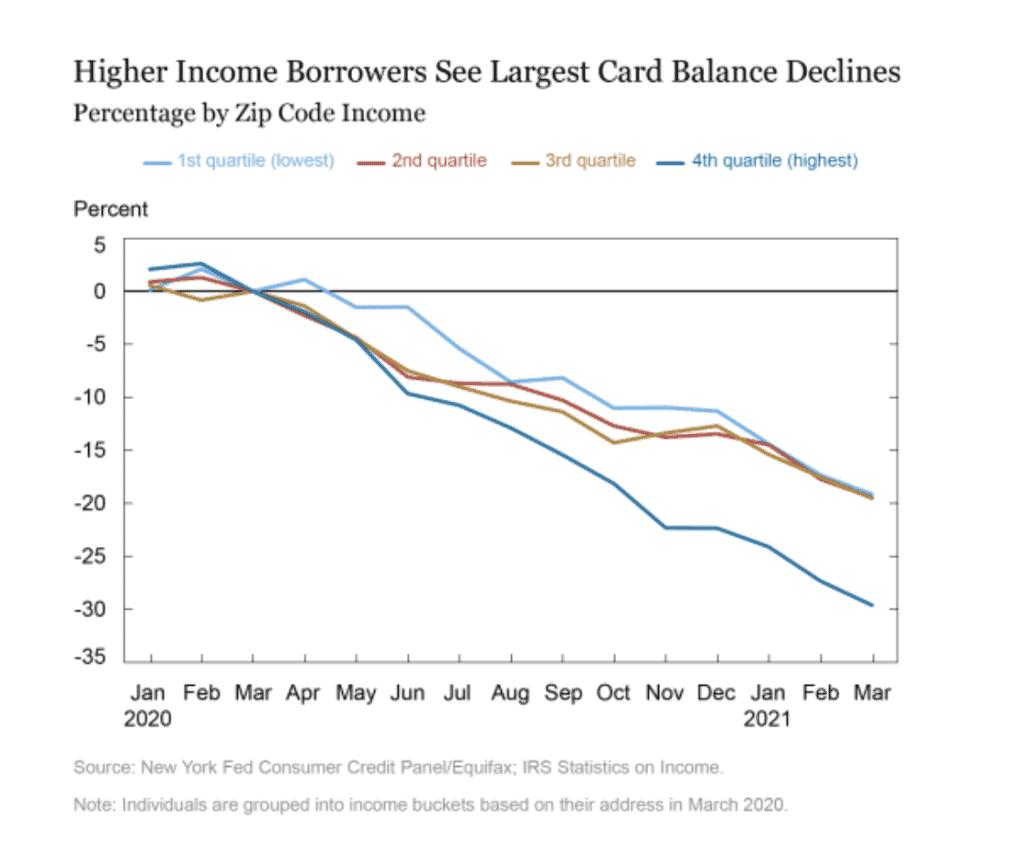

Of course, as we discussed in last week’s post, the benefits of mortgage forbearance did not fall equally across all consumer groups. With regard to credit card balance pay-downs, shown below, those in the highest income quartile cut their monthly cut their monthly credit card balance by 30 percent in the past twelve months. By contrast, outside of the highest quartile, credit card balances fell about 20 percent on average.

In next week’s post, we look at how small businesses turned to personal credit to sustain themselves during the pandemic.

SOURCE

https://libertystreeteconomics.newyorkfed.org/2021/05/what-happens-during-mortgage-forbearance.html

To learn more about Recovery Decision Science contact:

Kacey Rask : Vice-President, Portfolio Servicing

[email protected] / 513.489.8877, ext. 261

Error: Contact form not found.