In our last post, we began addressing the impact of the whopping student loan debt on Americans of all ages.

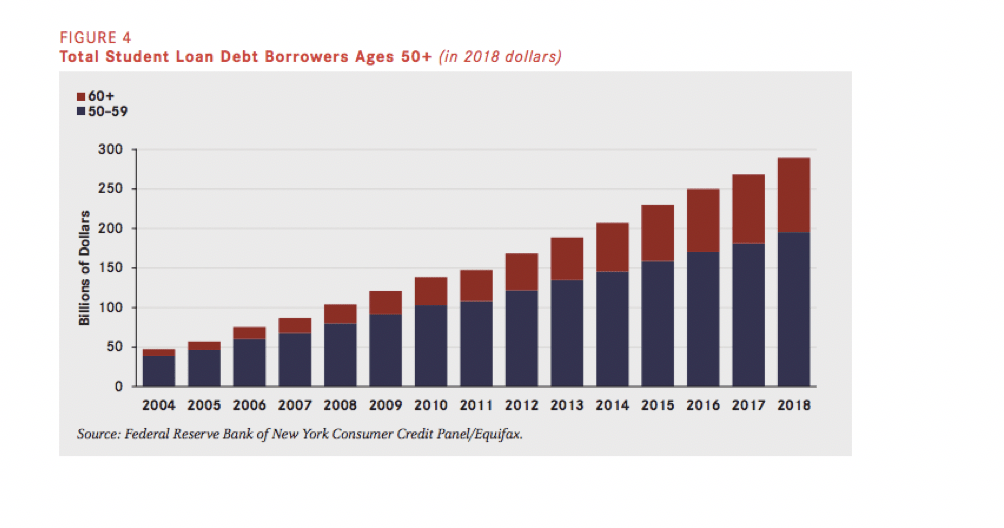

As we discussed, the American Association of Retired Persons (AARP) reports those over 50 now account for approximately $289 billion, or 20 percent, of the $1.6 trillion in outstanding debt.

And most borrowers in the over-50 age bracket aren’t carrying debt for their kids: Most older borrowers are holding loans for their own educations.

In 2015, 5.3 million student loan borrowers ages 50 and older had outstanding federal student loan balances for their own education, with default rates on the rise.

Data compiled by the Government Accountability Office (GAO) found that federal student loan borrower defaults increase with age. According to the GAO, in 2015, there were 870,000 borrowers ages 65 and up, 37 percent of whom were in default; five percent of those in default were subject to offset of federal payments.

Approximately 29 percent of the 6.3 million borrowers ages 50–64 were in default, of which three percent were subject to offset. There were 37.4 million borrowers under age 50, 17 percent of which were in default, and two percent of those in default were subject to offset.

Additionally, defaults on Parent PLUS loans have increased in recent years and repayment rates have slowed.

PLUS – Parent Loan for Undergraduate Students — loans allow parents and guardians to take out a loan directly from the federal government to cover up to the full cost of attendance for dependents.

Prior to 1992, Parent PLUS loans were capped at $3,000 per academic year and had an aggregate limit of $15,000. PLUS loan limits were removed in 1992, so parents are now allowed to borrow up to the full cost of attendance.

Although Parent PLUS loans require a credit history check, they are not underwritten to ensure that borrowers can afford to repay them. This can result in unaffordable loans that lead to default, especially considering that parents’ incomes are likely to go down upon entering retirement.

Five years ago, default rates were higher for other federal student loans than for Parent PLUS loans. However, this may change in the future as more parents take out higher amounts of Parent PLUS loans.

Research examining Parent PLUS loan performance indicates that parent defaults have increased in recent years and repayment rates have slowed. For many families, the amount they owe increases over time because they are not paying enough to cover interest and pay down principal. This can occur when a loan is in deferment or forbearance or for some borrowers who are in income-based repayment plans.

An AARP survey asked respondents ages 50 and older who had taken out a Parent PLUS loan and who had made a payment over the prior five years whether they ever had any difficulty making payments. Researchers considered signs of difficulty to include one or more of the following: Making at least one late or partial payment, missing at least one payment, and contacting the servicer about lowering the monthly payment. Overall, nearly one-third (32 percent) of people ages 50 and older exhibited at least one sign of difficulty.

Clearly, student loan debt is an intergenerational problem. Repayment periods required to pay off the debt are longer today—now often 20 or 25 years, double the repayment period of prior generations. As a result of these higher balances and longer-duration loans, parents and grandparents who borrow or cosign often sacrifice their own financial security in retirement. Increasingly, borrowers are defaulting on their loans and facing wage garnishment and offsets of their federal tax refunds or Social Security payments.

SOURCE