In today’s post, we continue our exploration of the NY Fed’s study on Homogeneity in America. Specifically, we look at how merit-based financial aid for college students passes through to debt and consumption, such as spending on credit cards, automobiles, homes, etc.

In an earlier report from 2019, the Fed shared that eligibility for merit-based financial aid has no impact on whether students decide to go to college, but did lead to a lowering of debt obligations for those students who did attend.

This year’s follow up report does a deep dive into the impact merit-based financial aid has on the most critical areas of personal finance.

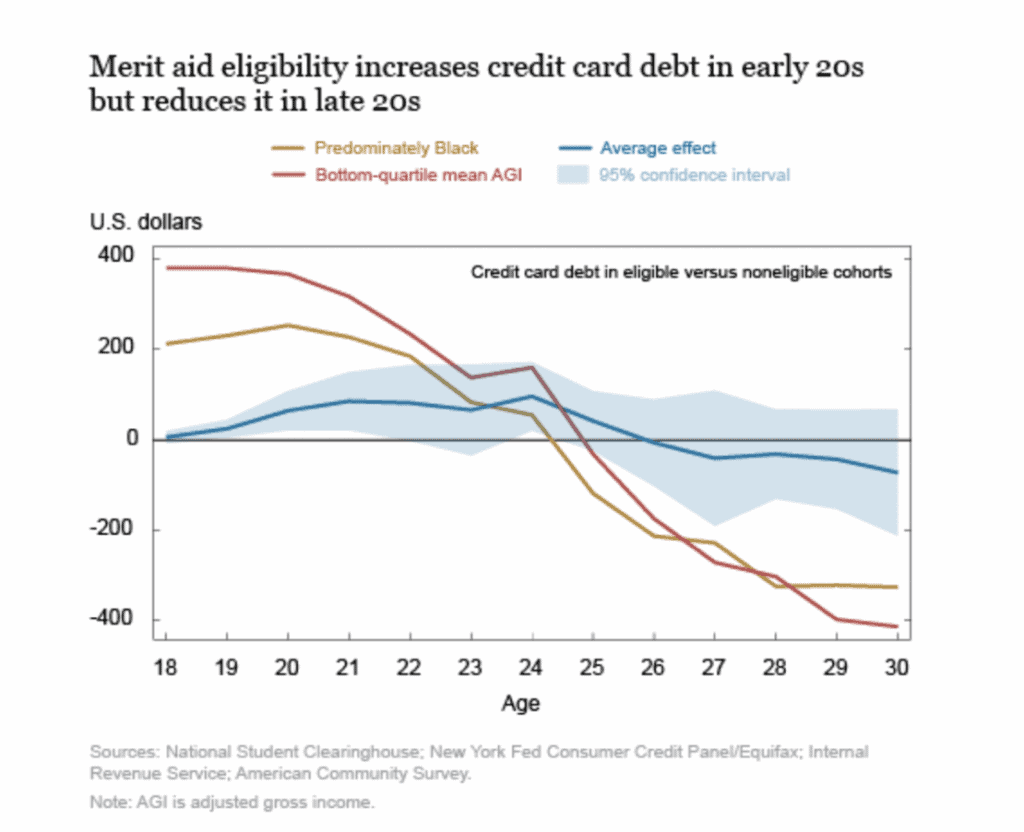

CREDIT CARD USAGE

The first area this report covers is student use of credit cards. In the chart below, we see:

- For merit-aid-eligible individuals there is an immediate impact on short-term spending captured by credit card debt.

- It is estimated (not shown on chart) that the merit-based aid amounts to $100 in incremental credit card spending, or an increase of about 12 percent of the mean credit card balance.

- Increases in early 20s credit card spending is consistent with a direct substitution for educational expenses. In other words, some of the money not spend on college tuition is directed to other consumer purchases.

- The shift of tuition savings to credit card expenses has also had an impact on delinquency rates. Namely, by age 25, an individual in a merit-eligible cohort is 1.8 percentage points more likely to have been at least 90 days delinquent, a 9 percent increase versus the mean.

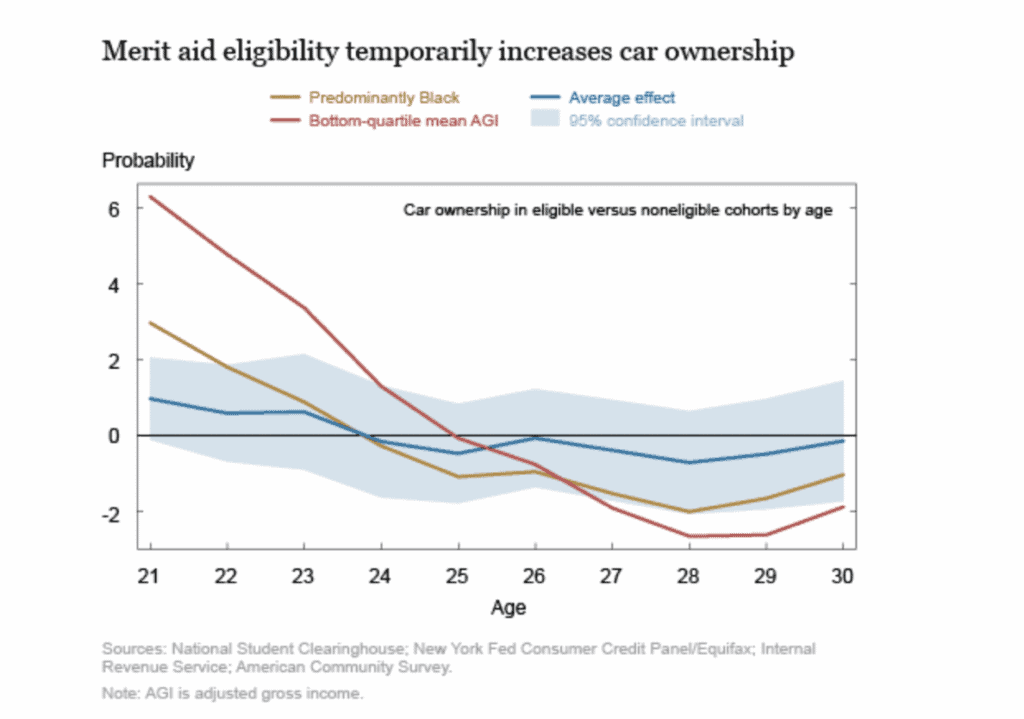

AUTOMOBILE PURCHASES

Currently, 85 percent of all car purchases are financed through a car loan.

With regard to those qualifying for merit-based financial support:

- Individuals belonging to merit-based-eligible cohorts show an increased propensity to buy cars at the typical college age.

- Individuals from low-income and predominately Black neighborhoods are much more likely to buy cars in their early-to-mid 20s than peers in other eligible cohorts.

- Thus, the trend shows more car-buying while in college, but possibly less buying and faster paying down of debt post-college. This pattern of substitution into car debt when the students have more cash in hand and a reversal later in life is especially prominent for individuals originating from low-income zip codes.

TOTAL DEBT

Total debt is here defined as all types of debt, including student loans, auto, mortgage and home equity lines of credit, credit card, retail card and consumer finance debt.

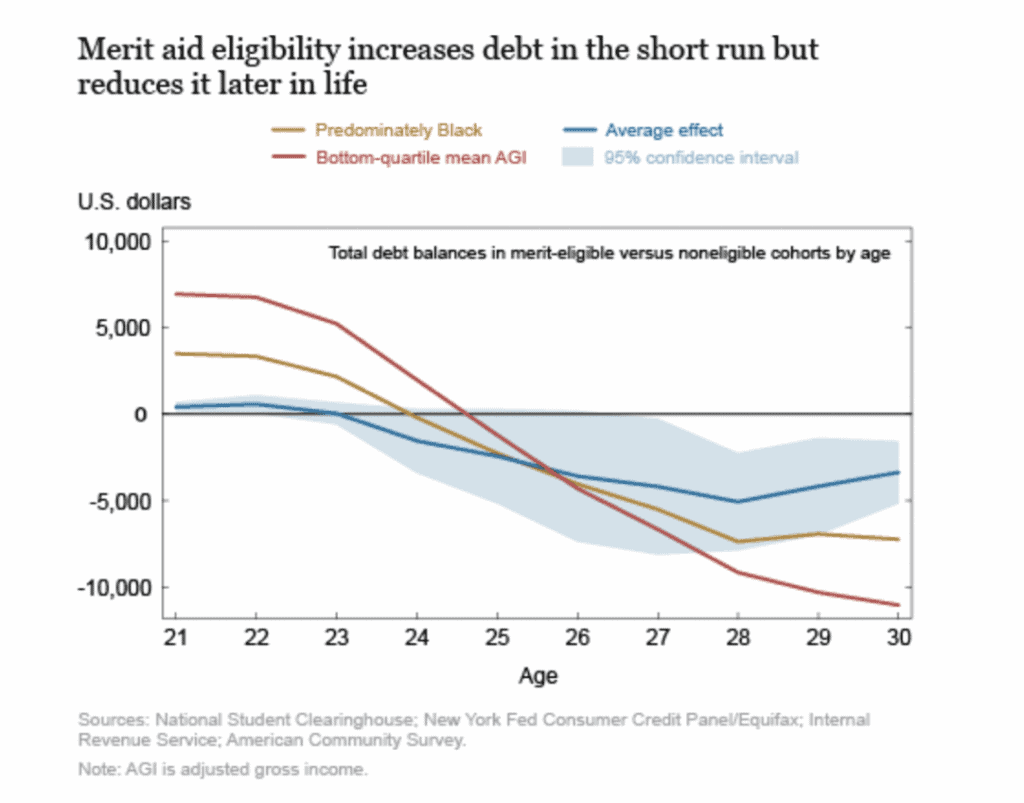

As illustrated in the chart below:

- There is an initial increase in total debt of merit-eligible cohort members in their early 20s, despite a reduction in their student loan balance. Then, as this cohort moves into their late 20s, we see a decline in their total debt burden.

- These patterns are stronger for individuals from predominately Black zip codes. Reduced college costs (due to merit-aid eligibility) drives consumption up even more in their early 20s, while leading to a further reduced overall debt burden in their late 20s. This decline in total debt is not only about lower student debt, but also about reductions in mortgage, auto and credit card debt.

Next week we complete this series on Homogeneity in America with a broad look at the role Medicare plays in improving financial health in the U.S.

SOURCE

Rajashri Chakrabarti, William Nober, and Wilbert van der Klaauw, “Do College Tuition Subsidies Boost Spending and Reduce Debt? Impacts by Income and Race,” Federal Reserve Bank of New York Liberty Street Economics, July 8, 2020, https://libertystreeteconomics.newyorkfed.org/2020/07/do-college-tuition-subsidies-boost-spending-and-reduce-debt-impacts-by-income-and-race.html.

Error: Contact form not found.