We’ve written extensively in this blog about issues related to attending and paying for college. Feel free to check out any of the following posts:

- Measuring Racial Disparity in Higher Education and Debt Outcomes

- Do College Tuition Subsidies Boost Spending and Reduce Debt Impacts by Income and Race?

- Student Loan Debt by Neighborhood Income

In today’s post we look at the “value of college” question from another angle: Does the quality of the college have an impact on both education and long-term income prospects? To get at the answer, we summarize learning from several posts published recently on the St. Louis Federal Reserve website.

For their two-part series, the St. Louis Fed used data from National Longitudinal Surveys of Youth done in 1979 and 1997. Or put another way, they studied Baby Boomers and Millennials entering college in about 1980 and 2000, respectively.

The authors divided colleges into four categories based on average SAT scores:

- Type 1: Community colleges offering transferrable associate degrees

- Types 2-4: Four-year colleges grouped by freshman’s average SAT scores

STUDENT LEARNING ABILITY

The authors understood that simply looking at graduation rates by college type could be misleading. That’s because not all students are alike. So, they adjusted for something they referred to as student learning ability, defined as:

“All student characteristics at the time of high school graduation that matter for both their academic success and labor market success (e.g., college preparedness, work ethic, grit, ambition).”

Aptitude tests were used to determine student learning ability scores. These scores were then used as the basis to compare outcomes across college types.

DOES COLLEGE QUALITY MATTER?

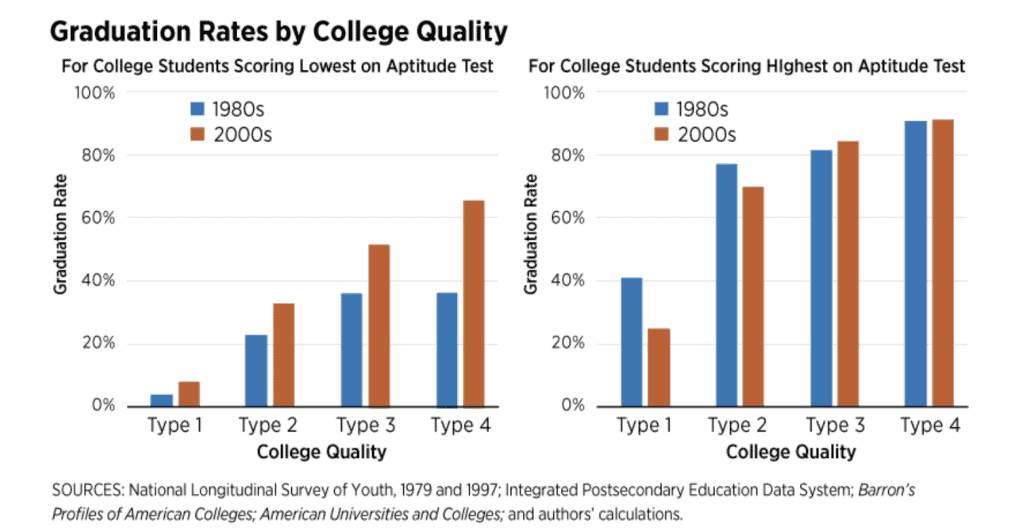

In general, college quality matters greatly. When looking at the older cohort (Boomers), choosing the highest quality, four-year college increased the student’s likelihood of graduating by 50 percentage points, relative to attending a community college. For Millennials, the probability of graduating increased by 63% for those who attended the highest level, four-year college.

The charts below look at graduation rates by college type, and after factoring in student learning ability.

The key learning:

- For students at the lower end of the student ability scores (left panel), getting into a higher quality college significantly improved graduation rates, especially for Millennials.

- The right panel, looking at those with the highest student learning ability, reveals higher graduation rates across all college types, across both age cohorts.

With regard to earnings (not shown in their posts), the older cohorts who attended the highest level, four-year college earned 5 percent more than those who graduated from the lowest-quality four year college. Millennials, on the other hand, earned 10 percent more by attending a higher-quality, four-year college.

The second part of the St. Louis Fed’s study of college quality focused on the relationship between the importance of college quality and how students are “sorted” based on learning ability.

The authors suggest that there is a widening learning ability gap between the low and high tier colleges, and that it is being driven by several key factors:

- The College Premium: Compared to the older cohort, Millennials faced a higher graduation premium (i.e. benefits of attending college). This explains why Millennials enrolled in college at a higher rate (57%) than did Boomers (46%). But what this also means is that more Millennials, with lower aptitude test scores, and from medium to higher income families, wanted to enroll. As a result, four-year schools, especially those of higher quality, increased their admission standards, which forced more lower-ability high school graduates to enroll in lower-tier schools, especially community colleges.

- Family Finances: Average tuition for Millennials more than tripled compared to tuition for the older cohorts. Even after factoring increases in scholarships and grants, the tuition differential between cohorts was double. But while tuition increased, limits on borrowing for subsidized government loans remained essentially unchanged. This meant that younger students had to lean on their parents for financial support, work more hours and, ultimately, enroll in less expensive colleges. Net, lower ability students from lower income families were disproportionately impacted as a result of this “downgrading of college choice.”

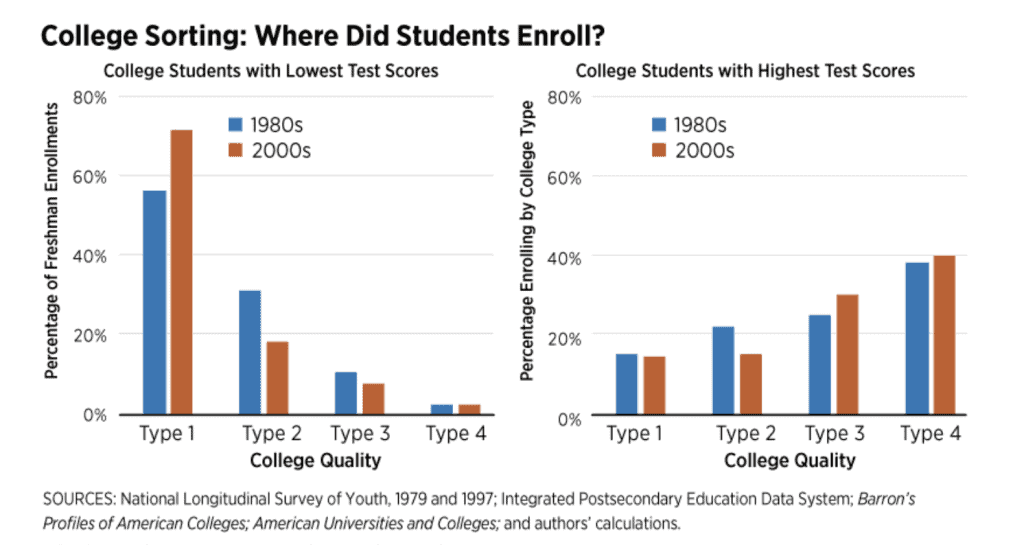

The chart below puts the sorting issue in more perspective:

- We see from the panel on the left that those with the lowest aptitude test scores (in both age cohorts) tended to enroll in either community college or the lowest level four-year college at much higher rates. More than half of Boomers with low test scores enrolled in community college. But, as a result of some of the sorting factors mentioned above, more than 75% of Millennials with lower test scores had to start their college journey in community college.

- In looking at the highest aptitude students on the right, we see, as would be expected, higher enrollment in better-quality schools for both age cohorts. However, it’s worth noting the distribution of enrollment is generally flatter for the higher testing high school graduates. This, of course, suggests that better prepared and equipped students have greater options and flexibility compared to students at the lower end of the ability spectrum.

As we see from the St. Louis Fed study, the quality of the college students attend is a significant factor when it comes to graduation rates, regardless of the age cohort. But, as the demand for college degrees intensifies, especially for Millennials, those who lack both the aptitude and financial means, are often forced to compromise as to how they begin to pursue their career goals.

Kacey Rask : Vice-President, Portfolio Servicing

[email protected] / 513.489.8877, ext. 261

https://www.stlouisfed.org/on-the-economy/2020/december/staff-pick-college-quality-matter