From the earliest stages of the pandemic, Recovery Decision Science has covered the impact COVID-19 has had on various aspects of the economy. Most notably, RDS created an extensive, interactive workbook on its Tableau Public page that tracks U.S. unemployment from a variety of perspectives. Also, this blog has covered the economic disruption created by the pandemic, especially as relates to economic inequality based on race and income.

Today, we look at unemployment through a different lens, namely, the effect COVID has had on small business closings.

DEFINING SMALL BUSINESS

Generally, a small business is defined as a “privately-owned corporate, partnership or sole proprietorship that has fewer employees and less annual revenue than a corporation or regular size business.” In this regard, the term “small business” is relative, based on standards set by specific industries. For example, a small business in the service/retail sector would be one in which annual revenue does not exceed $6 million.

SMALL BUSINESS CLOSINGS

There is a renewed sense of optimism as America slowly pulls out of the worst of the pandemic. Still, national unemployment hovers at 6 percent, nearly double the pre-pandemic rate. And, in the most severely-impacted industries, such as food service and hospitality, unemployment stands at around 13 percent, more than twice the national average.

So, the question persists, in light of the generally-upbeat economic story of recent months, will small businesses rebound to pre-pandemic levels, both in terms of revenue and employment?

The Federal Reserve explored this question in a recent study. And, unfortunately, the news is not encouraging.

For this study, the Fed pulls its data from Homebase, a scheduling and time tracking tool that is used by about 100,000 mostly small firms, across leisure, hospitality and retail sectors. To be included in the baseline for this study, a business had to be “active” during a consecutive, three-week period starting on February, 2, 2020. A business is considered active if it recorded positive employment and at least 40 total hours worked in a given week.

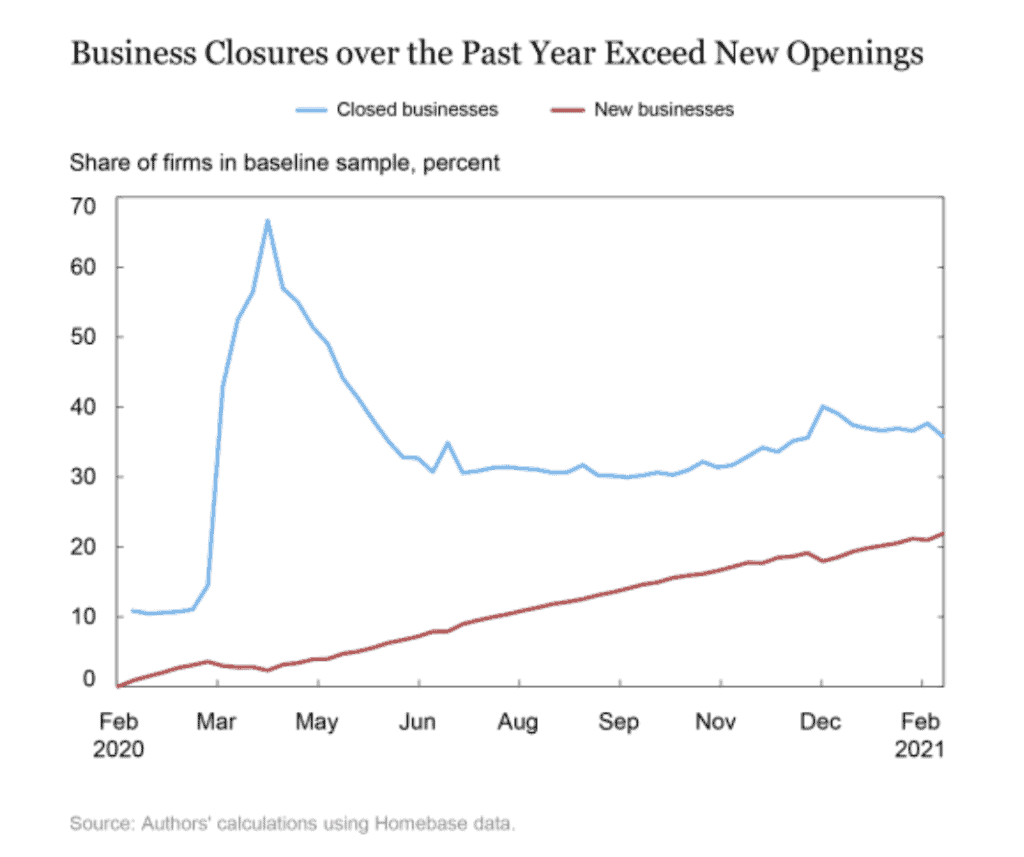

As you can see, at the height of the crisis in April 2020, about 60 percent of American small businesses closed (defined by zero hours worked or NOT in the same for two consecutive weeks). After falling to 30 percent closures in mid-summer, the level creeped back up to its current level of 35 percent of small businesses still closed as of February, 2021.

The red line shows NEW business openings over the past 12 months growing to about 20 percent of firms in their baseline sample. But still, this new business growth falls well short of what is needed to compensate for the business closures (and job losses) since the start of the pandemic.

OVER TIME

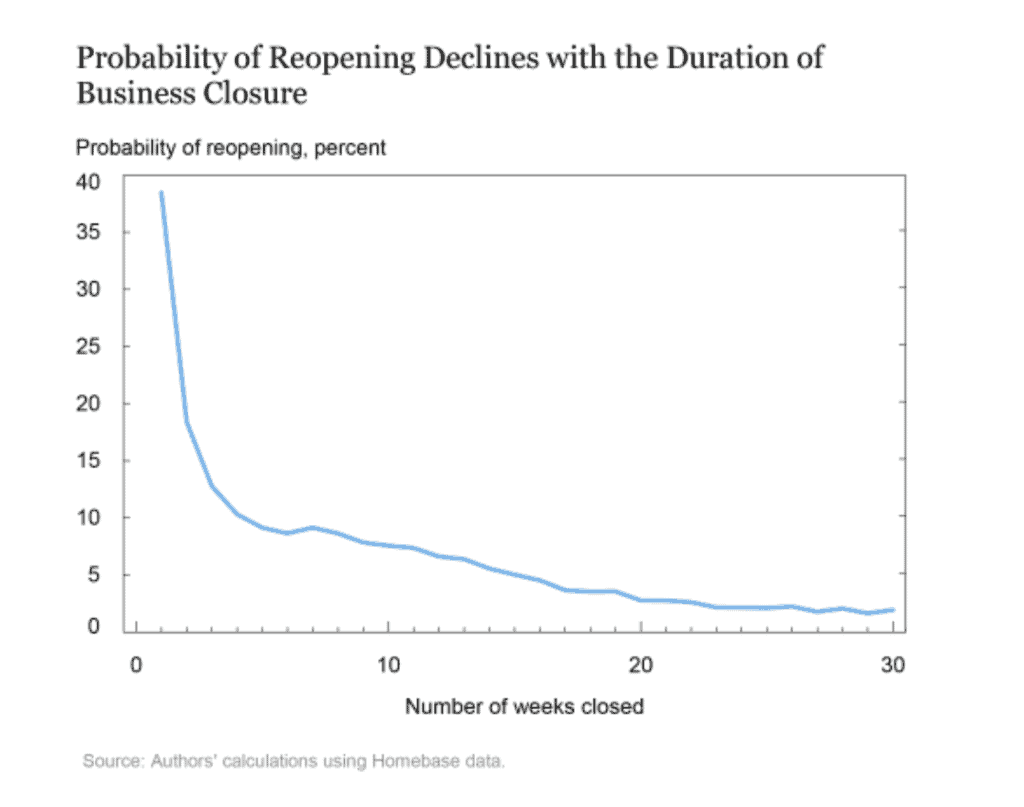

To compound the challenge small businesses face, the study also revealed (not surprisingly) that the longer a business remains closed, the less likely it is that the business will ever reopen.

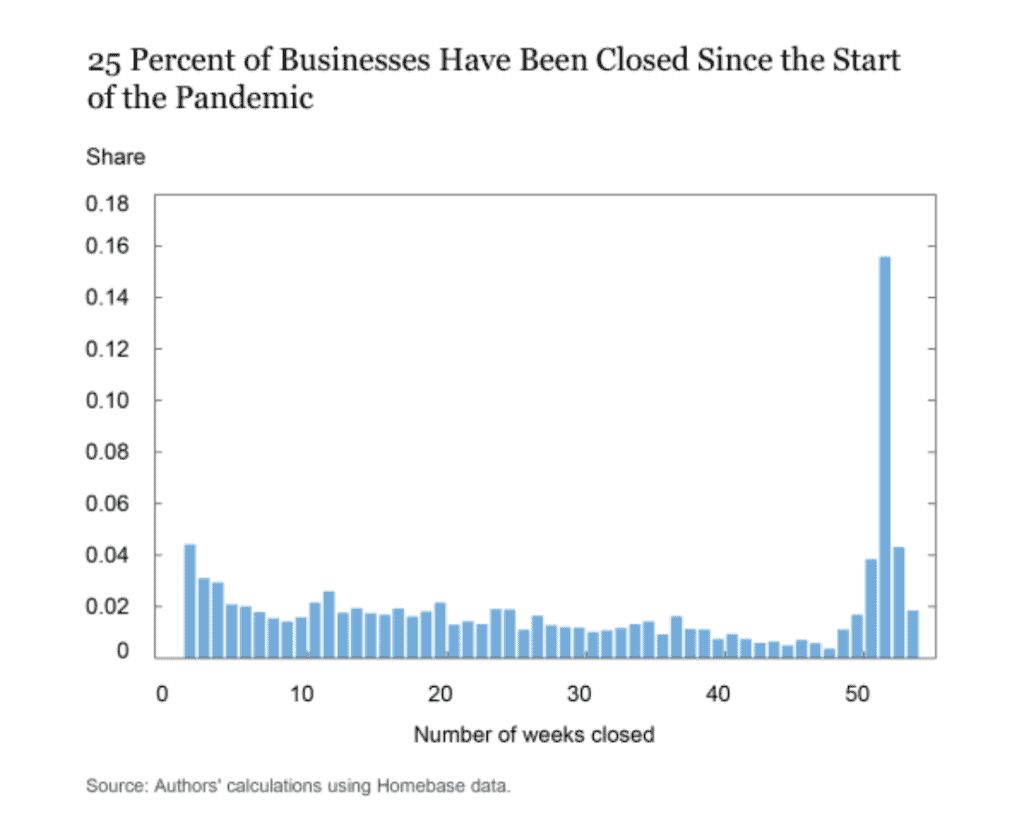

In the first chart, we see that 25 percent of businesses that closed since the start of the pandemic remain closed today. The second chart shows that the longer a business stays closed, the less likely it is to reopen.

Why is it so difficult for small businesses to rebound? There are two primary reasons. First, a closed business must still incur fixed costs, such as long-term rental contracts. With each successive month of closure, these fixed costs eat into the business owner’s capital. In fact, a survey of more than 5,800 businesses by the Proceedings of the National Academy of Science (PNAS) illustrated the fragility of many small businesses. PNAS found that three-quarters of the respondents had enough cash-on-hand to last two months, and the median firm with monthly expenses exceeding $10,000 had only enough cash to last about 2 weeks.

The second reason that it’s difficult for small businesses to bounce back from something as disruptive as the pandemic is that extended closings mean a loss of their customer base. Given the challenge of building and asustaining a customer base in today’s hyper-competitive marketplace, it is increasingly difficult (and costly) to replace customers who leave your business.

REHIRING

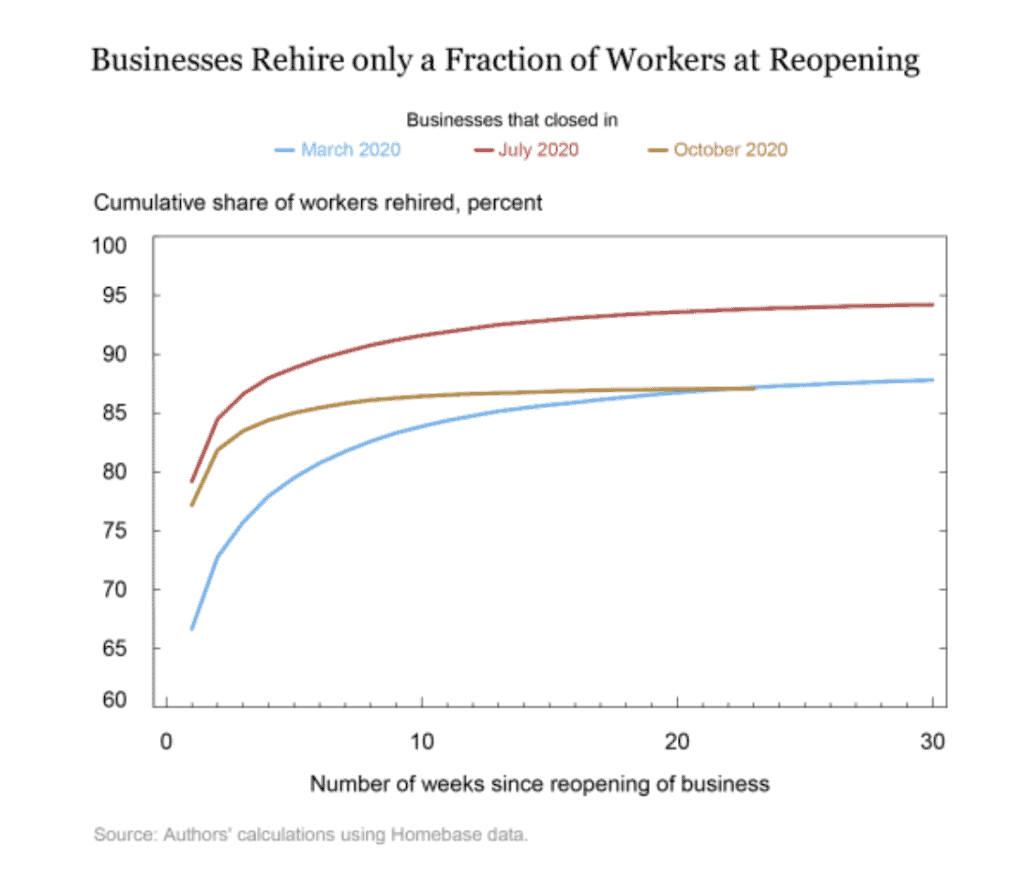

The Fed’s study also looked at rehiring levels upon a business’ reopening. The chart below measures “rehiring shares” for businesses that closed in March (Blue), July (Red) and October (Gold) of 2020. What we see is that 70-80 percent of workers terminated at closure are rehired immediately upon reopening. But, over time, the speed of rehiring levels off.

SUMMARY

We close by sharing a few distressing data points that were not illustrated in the study. The Fed employed a panel regression to predict the fraction of currently-closed small businesses that are likely to reopen, along with the fraction of their workforces that might be rehired. The analysis revealed:

- Only about 3 percent of currently closed businesses expect to be reopened

- Of those that reopen, it is estimated that about 35 percent of their laid-off workers will be rehiredover four weeks

- Combining these variables, the Fed estimates that only about 4 percent of the workers of currently closed businesses will be rehired

We’ll track updates to these predictions in future posts.

SOURCE

https://www.pnas.org/content/117/30/17656

To learn more about Recovery Decision Science contact:

Kacey Rask : Vice-President, Portfolio Servicing

[email protected] / 513.489.8877, ext. 261

Error: Contact form not found.