In our prior post, we discussed the large and persistent gap in wealth between whites and blacks.

The Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland theorizes the wealth gap might simply be the result of a historical wealth gap so large it hasn’t yet had time to close. Wealth takes time to accumulate.

The Fed studied a variety of obstacles to wealth equalization, such as savings rates, inheritances, rates of return on investments, and income. If blacks and whites differ on any of these dimensions, it could explain the persistence of the wealth gap.

There’s no proof black households earn lower returns on the same assets as white households. However, portfolios held by black households were more concentrated in low-average-return assets.

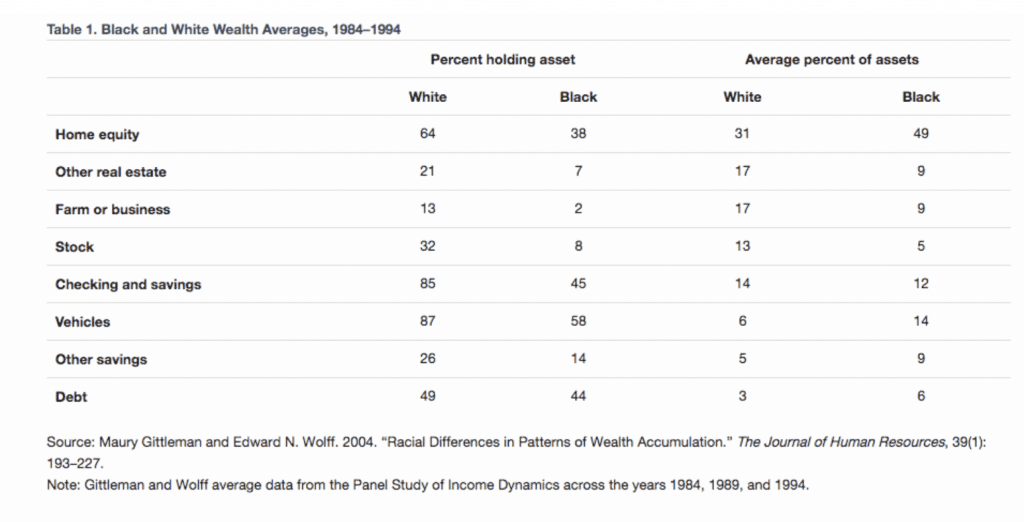

Table 1, below, displays the average share of asset types held across race and years from 1984 to 1994. First, we might compare the percentages of black and white households that hold each type of asset (columns 1 and 2). Notice that white households hold a larger fraction of each asset category than do black households. For example, 64 percent of white households hold home equity, while only 38 percent of black households have wealth in the form of home equity.

Second, the Fed compare the types of assets black and white households hold (columns 3 and 4). This comparison shows that the assets of white households are more concentrated in real estate, business, and stocks. These assets tend to be riskier than the other categories, but they also provide a higher average return.

Table 2 displays the same information for 2015 and shows that, despite improvement in the fractions of asset ownership by black households, the same portfolio imbalances persist. One explanation for the higher concentration of low-average-return assets in black households’ portfolios could be those households’ lower wealth levels. Higher returns are associated with higher risk, and the less wealth a household has, the less risk it may be willing to take with its investments.

While portfolio differences are real and impactful, portfolio differences are not the most significant factor contributing to the racial wealth gap.

Inheritances are another factor that explains the wealth gap. If white households had more wealth in the past than did black households and bequeathed their estates to their children, we should expect the wealth gap to persist for several generations.

The magnitudes of differences in inheritances have been found to be large. One study showed far fewer black households that reported receiving an inheritance compared to white households. Of those who did, the average value was about five times smaller than that of their white counterparts.

Still, only 10 to 20 percent of the racial wealth gap can be accounted for by the difference in intergenerational wealth transfer. Few households, black or white, receive what could be considered large inheritances.

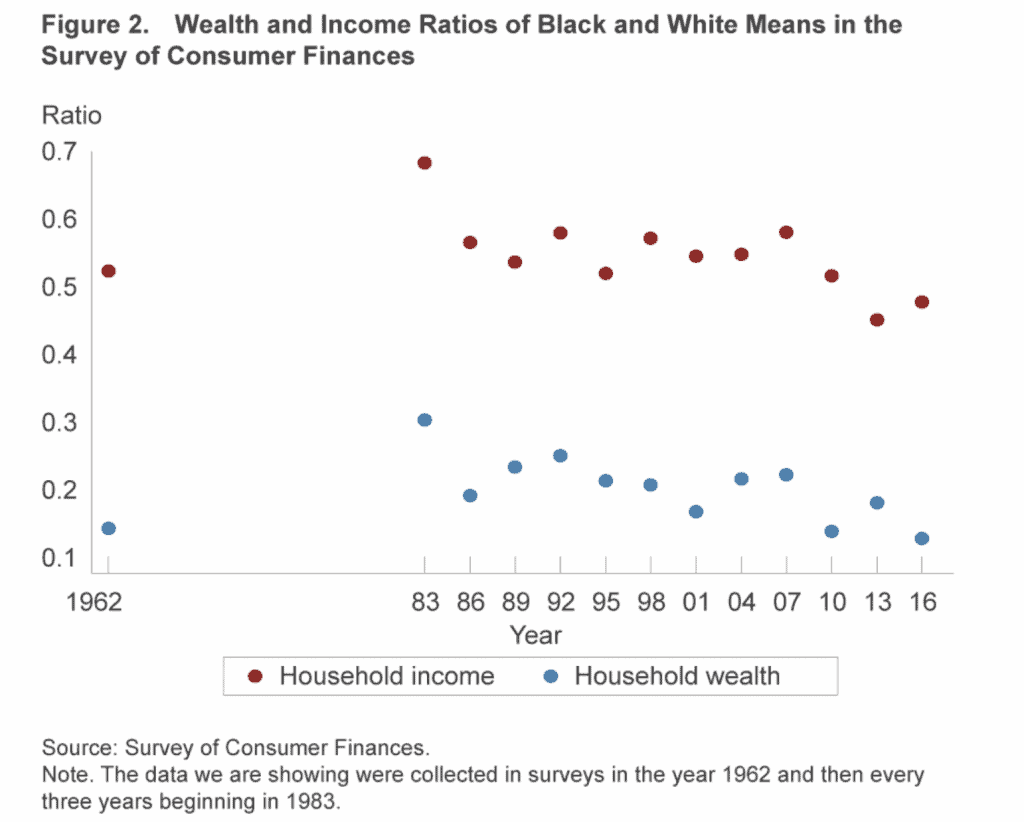

Let’s take a look at the income gap by returning to Figure 2 below from the previous post on this topic.

Note the sizeable gap between the average income earned by white households and the average earned by black households: The ratio of labor income between black and white households was roughly 52 percent in 1962, and grew to 58 percent in 2007 before falling steeply after the Great Recession.

Since neither the income gap nor intergenerational wealth transfer can explain the racial disparity, other factors are clearly at play. In our next post, we examine a less traditional way of examining the reasons for the gap.

SOURCE