For years, and as the population has aged, end-of-life medical spending has been a topic of considerable interest, to those in financial services.

One of the accepted beliefs is that patients in the last year of life account for a disproportionate share of Medicare spending. But this is often a topic for debate. Forbes Magazine for example, has run contradictory articles about end-of-life spending:

- Why 5% of Patients Create 50% of Health Care Costs, Michael Bell, Jan. 10, 2013

- Medicare May be Spending Far Less On End of Life Patients Than We Think, Howard Gleckman, Oct. 11, 2018.

As an estimated 74.1 million Baby Boomers, still the largest living generation, become senior citizens, we turn to the Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond for a more measured assessment of this issue.

In November, the Richmond Fed released a study documenting end-of-life medical expenses: examining their contribution to aggregate medical spending, how they affect household behavior and the efficacy of spending at this stage of life.

In the first of this two-part series, we will address the effect of end-of-life spending on households while in our second part we will assess chronic disease in senior citizens and the implications for both end-of-life spending and spending in aggregate.

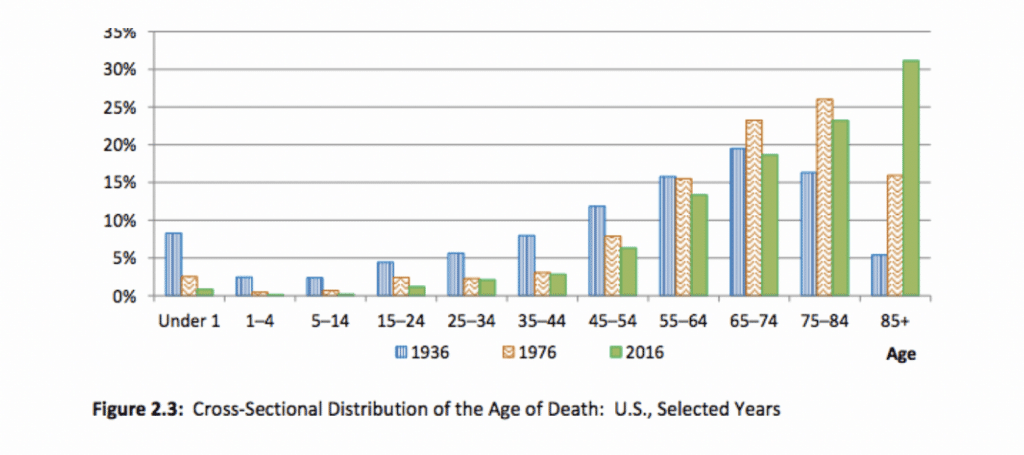

We set the stage by reviewing changes in mortality over the last century, during which there have been.profoundchanges in health, longevity, and medical care. These changes have had dramatic changes on death and the costs associated with death. These developments includedreductions in infant mortality and death from infectious disease. Because of these declines,death increasingly occurs at older ages and is increasingly associated with chronic conditions that are often costly. By 2016, 73 percent of those dying in America were at least 65 years of age and 31 percent were at least 85, as demonstrated below.

Average medical spending from all payers during the last 12 months of life was $80,000 in 2014 dollars and spending during the last three calendar years of life was $155,000. These totals are roughly double those incurred in the final 12 months. Thus, the spending of those who die is far from fully concentrated right at the time of death. This suggests that the high cost of dying is due less to last-ditch efforts to save lives than to spending on chronic conditions, which are associated with shorter life expectancies.

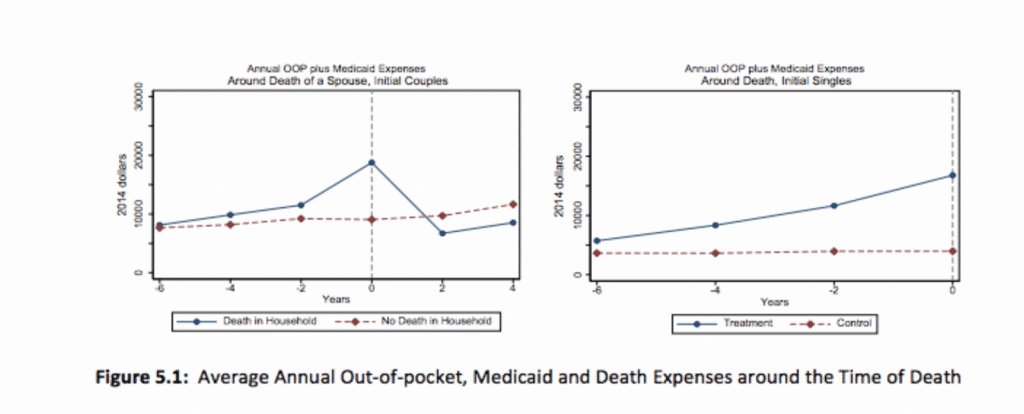

The Fed found that end-of-life spending places a significant financial burden on many households and changes saving and spending behavior. The left panel of Figure 5.1 below shows average annual medical spending for married households that lose a spouse from six years prior to death to four years after death. The right panel shows average annual spending for singles (including those widowed, divorced, and never married) in the six years prior to their deaths. Six years prior to a household death, average out-of-pocket plus Medicaid spending is $8,000 per year for couples. This spending rises in the years leading up to death, reaching $19,000 in the period the death is recorded. 1After the period of death, medical spending returns to its original level. The right panel of Figure 5.1 shows that for singles, medical spending rises from $6,000 six years prior to death to $16,000 in the year the death is recorded.

According to the Fed, many households with senior citizens draw down their wealth at a relatively slow rate. One explanation is that they are saving money as protection against the possibility of high medical expenses.

While many older Americans run down their assets to obtain long term care (LTC,),the Fed report debunks the trope that some seniors intentionally divest themselves so as to qualify for Medicaid. The report references a 1995 study showing more seniors are likely to receive asset transfers to avoid having to use Medicaid rather than to divest themselves.

Medicaid reimburses nursing homes and LTC facilities at rates lower than market, often resulting in a lower standard of care. A 2017 survey of Vanguard financial customers showed the desire to avoid Medicaid-funded care is a motivator for savings behavior.

In spite of the discomfort surrounding Medicaid-funded care, purchase of private LTC insurance remains modest, with only about 10 percent of older households opting for it. There are several reasons for this trend.

First, many seniors prefer to save their wealth as their own form of insurance as well as giving them the ability to leave bequests, according to the report.

Second is the issue of adverse selection: Those most likely to need coverage are most likely to apply but often have conditions preventing them from qualifying for insurance. Even those who do qualify face high premiums and those seniors who switch from informal care – think family members – to formal further drive prices up.

Finally, a third explanation may be that Medicaid – the payer of last resort – covers only the expensesother insurance does not, providing little incentive for households to purchase private LTC insurance. A 2008 study referenced by the Fed report estimated Medicaid significantly reduced the return on LTC insurance for 75 percent of single households.

Next week, we turn our focus to the impact chronic disease has on end-of-life spending.

Sources: