In 2018, the Federal Reserve launched an initiative to raise awareness and encourage action against synthetic identity payments fraud, the fastest growing type of financial crime in the U.S. In 2016 alone, the Fed estimates it cost lenders $6 billion.

For those unfamiliar with it, synthetic identify fraud is a fancy name for a type of scam which involves combining fabricated data with authentic personal information. Creators of the fraudulent identities use the information to open accounts that can stay open for years, before they eventually max out the credit line, vanish, and leave the financial, health care, consumer or insurance institution on the hook.

Due to the increase in this type of crime and the significant risk to banks and financial institutions, we will spend the next few posts exploring the ramifications of synthetic identity fraud.

In the first, we will go into more detail about how synthetic identities are created.

Fraudsters leverage the personally identifiable information (PII) of individuals – such as children, the elderly or homeless – who are less likely to access their credit information and thus, discover the fraud. Synthetic identities can behave like legitimate accounts and may not be flagged as suspicious using traditional fraud detection models.

This affords perpetrators the time to cultivate these identities, build positive credit histories, and increase their borrowing or spending power before “busting out” – maxing out the line of credit with no intention to repay. The operators of the fraudulent accounts can employ a variety of tactics to multiply their payouts. One such tactic is for the fraudster to claim identity theft on the fictitious identity, allowing charges to be reversed and credit lines reopened.

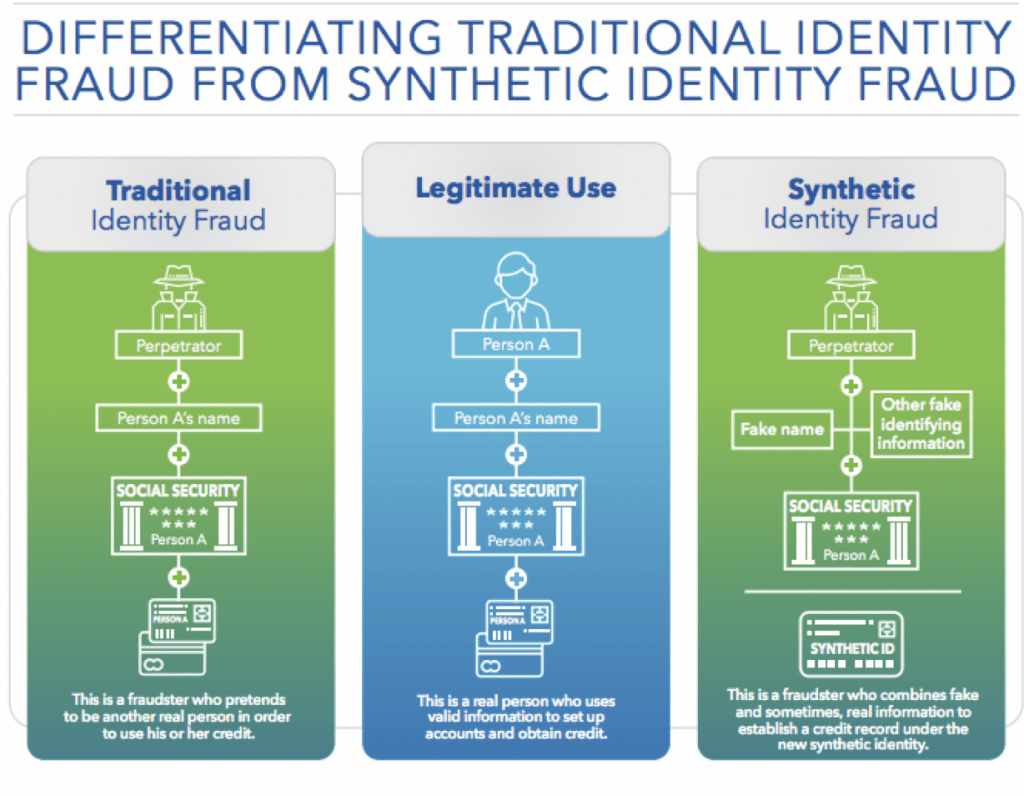

Synthetic identity fraud differs from traditional identity fraud, where a fraudster pretends to be another real person and uses his or her credit. Traditional identity fraud is typically detected and reported more quickly because the victim notices unusual charges on his or her financial statements.

The illustration below graphically shows the differences in the two types of fraud and legitimate accounts.

Several factors are responsible for the rise in synthetic identity theft, including the near-universal use of Social Security numbers (SSNs) as identifiers in the U.S.

The Social Security Administration (SSA) created SSNs to track an individual’s earnings and benefits but they have evolved into a principal way private industry and government agencies identify people and assess their legitimacy. Compounding the difficulty of determining if an individual is real, the SSA began randomizing the assignment of SSNs in 2011. This eliminated the geographical significance of the first three digits (also called the area number) and, in turn, the predictable, chronological significance of the remaining digits.

Another factor leading to fraud is the availability of PII, much of it exposed through data breaches. According to the Identity Theft Resource Center, the volume of PII exposed this way increased by 126 percent between 2017-2018 for an estimated 446 million records exposed.

Dark web marketplaces sell these breached records, including bank account login credentials, driver’s licenses, credit card numbers and SSNs. Major credit reporting company Experian reports an SSN costs fraudsters as little as $1, and it’s just $30 for an individual’s full identity package of name, SSN, birth date, account numbers and other data.

Third, gaps in the credit process benefit scammers. When a fraudster initially uses a synthetic identity to apply for credit at a financial institution or retailer, the entity sends an inquiry to one or more credit bureaus. The bureau creates a credit profile for the synthetic identity, which helps legitimize its identity even when credit is denied.

The fraudulent operator can also manipulate the credit ecosystem through piggybacking – adding a synthetic identity as an authorized user on an account belonging to another individual with good credit. In many cases, the synthetic identity acquires the established credit history of the primary user, rapidly building a positive credit score.

In our next post, we examine how financial institutions can detect synthetic identities.

SOURCE