In April, Congress passed the CARES Act to both stimulate and stabilize the U.S. economy in the midst of the unprecedented economic fallout from COVID-19.

CARES featured both direct cash infusions and forbearance on federally-backed debts. In an earlier post, we looked at the ways in which Americans used their CARES stimulus checks. Today, we review a recently-released report by the New York Federal Reserve on who benefitted from forbearance, and the impact on both their delinquency status and credit score.

Let’s start with the Fed’s definition of forbearance:

“Forbearance provides borrowers the option to pause or reduce debt service payment during periods of hardship, without borrowers risk of being delinquent.”

The CARES Act offered a six-month moratorium toward payments on federally-guaranteed mortgages and student loans. In addition, regulators encouraged lenders of auto loans and credit cards to voluntarily offer forbearance on payments. Below is a link to these voluntary guidelines.

For this report, the Fed focused on mortgages and auto loan forbearance.

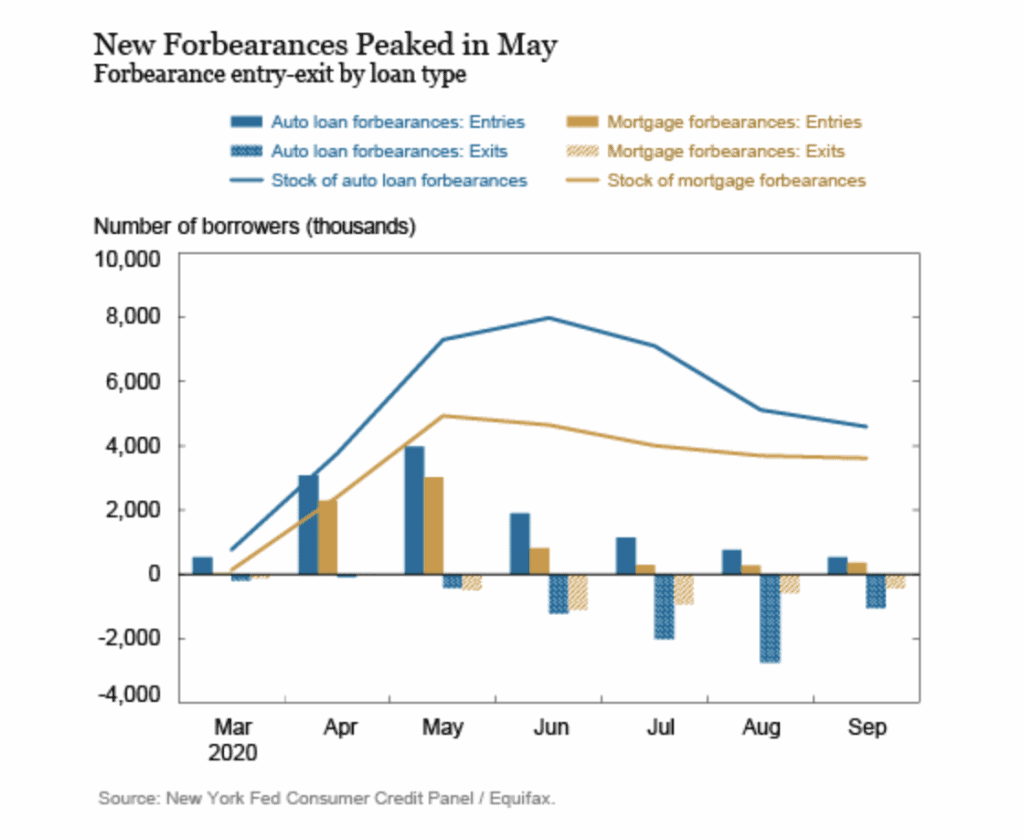

The chart below looks at “entry into and out of forbearance” on a month to month basis for mortgages (GOLD) and auto loans (BLUE):

- The SOLID lines show entry into forbearance for each type of loan, which, of course, are highest in April and May when unemployment was at its height.

- The SHADED bars show those who exited forbearance that month after having previously been in forbearance. Notably, many more people exited auto loan forbearance compared to mortgages, reflecting that auto loan forbearance varied by lender, and was not legally required.

- The lines illustrate the absolute number of people in forbearance for each type of loan from May through September. Auto loan forbearance peaked in June at 8 million, while May saw the highest point for mortgage forbearance at 5 million.

- Note that mortgage forbearance rates varied by the type of federally-backed mortgage:

- 4.2 percent-Government sponsored (Fannie May and Freddie Mac)

- 10.6 percent for Ginnie May (Federal Housing Administration and Veterans Affairs

- 4.2 percent for the balance of first mortgages, which include portfolio and non-agency MBS.

WHAT TYPE OF BORROWERS RELIED ON FORBEARANCE?

The Fed found two key characteristics among those who were granted mortgage and/or auto forbearance:

- Lower credit scores: on average, those receiving forbearance had credit scores that were 40 points lower than mortgage and auto loan borrowers who did not participate in forbearance (Auto-652 vs. 693; Mortgage-708 vs. 754).

- Higher balances: those individuals granted mortgage and auto loan forbearance had average remaining balances that were 30 percent higher than the non-forbearance group.

The report also looked at the relationship between loans in delinquency and forbearance.

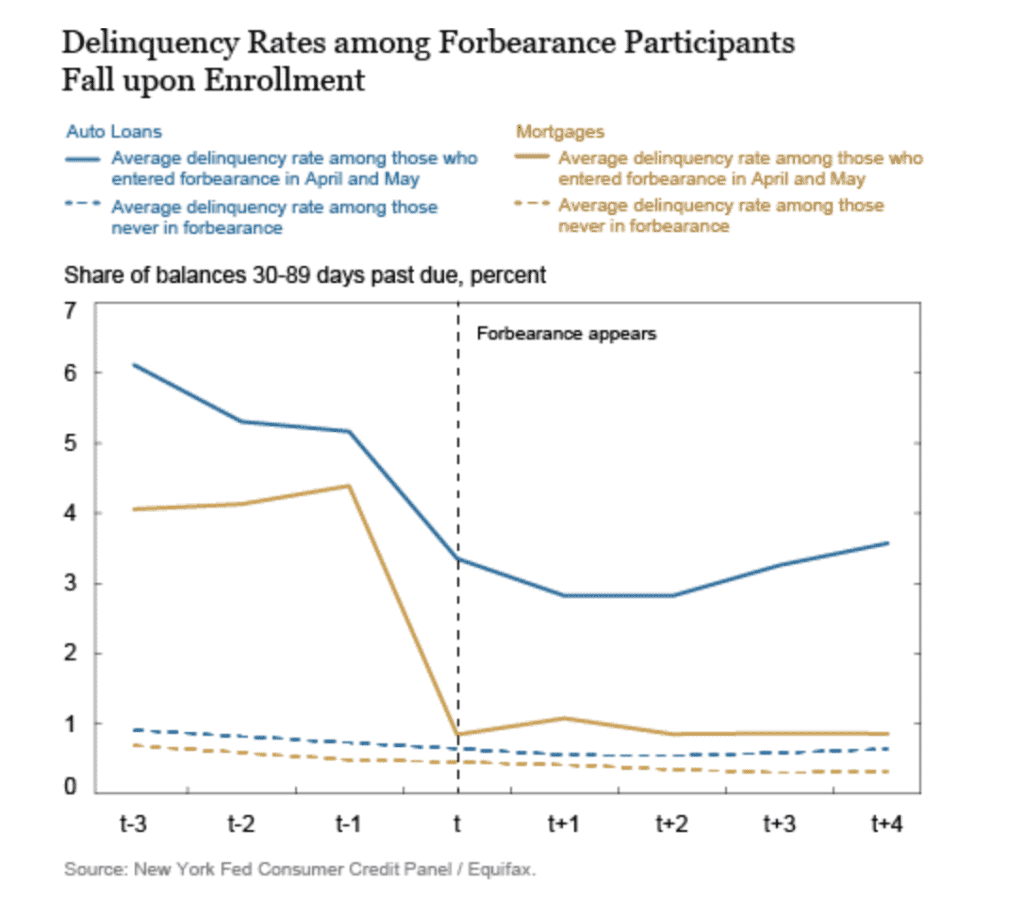

The chart below shows share of balances 30-89 days past due for:

- Those who enrolled in forbearance by May, 2020 (Solid lines)

- Those who did not participate in forbearance (Dotted lines)

As we can clearly see, once forbearance kicked in, there are sharp reductions in the balances that were 30-89 days past due. In fact, because of forbearance, many lenders converted previously-delinquent accounts to current because they did not have a payment due for the month.

Those delinquent borrowers whose accounts are converted to “current” through forbearance, enjoyed an average 48-point increase in their credit scores.

Of course, the big policy question is what happens now that cash transfers to households through CARES are ending and forbearances are set to expire. The issue is made that much more daunting as the second wave of the pandemic presses state and local governments to consider drastic measures to stem the spread of COVID (e.g., closing non-essential businesses).

We will continue to monitor the Fed’s analysis and update this report accordingly.

SOURCES

https://libertystreeteconomics.newyorkfed.org/2020/11/following-borrowers-through-forbearance.html